Extending Filibuster to Test Redis

This blog post was written by Eunice Chen, an undergraduate student who contributed to the Filibuster research project this Spring. Eunice did an excellent job extending Filibuster with a prototype of Redis support. She recently gradudated and we will miss her! Congrats, Eunice!

Summary

The automated resilience testing tool, Filibuster, lets developers test microservice applications for resilience against remote service unavailability. Filibuster achieves this by instrumenting remote procedure calls (RPC), commonly made using libraries like gRPC and Python’s requests, to perform a systematic exploration of all possible RPC faults for a given microservice application. However, the current version of Filibuster does not support fault injection when client libraries for databases are used to issue the remote procedure calls. In this article, I discuss work that I performed as part of a student research project in the Composable Systems Lab, part of the Institute for Software Research at CMU, to explore the viability of using Filibuster to test external services that use 3rd party client libraries such as Redis.

Introduction

As microservice applications become increasingly commonplace, it is critical to test the behavior of these applications under partial failure: when one or more of the services that the application depends on fails. If the application lacks the necessary error handling, it may completely fail rather than gracefully degrade when one or more of its dependent services fails. To address this issue, Filibuster systematically enumerates the possible RPC failures that an application might observe and then subjects the application to these failures, allowing developers to ensure correct operation under these failure scenarios during testing and prior to deployment.

Since microservice architectures are often used for web application backends, it is critical that Filibuster not only test services that communicate with other services, but also test services that communicate with databases, as databases play an important role in data persistence in backend services. Expanding Filibuster to support this style of fault injection on databases, and in the specific case Redis, will allow us to create a prototype and inform future research and engineering efforts towards this goal.

We started this work with two interesting questions:

- Could Filibuster be expanded to support database calls?

- How would this new support for database calls change the way the Filibuster tool interacts with microservice applications?

Let’s work with an example.

Example: Cinema Microservice Application

To explore what a design for database fault injection might look like, we decided to start by expanding one of the examples in the Filibuster application corpus with Redis, an in-memory data store often used as a cache. The Filibuster application corpus contains several example microservice applications, some of which are reproduced from industry to demonstrate different request patterns. Request patterns that are exemplified by the corpus range from retries on failure, to fallback requests, to using default responses on failure, as well as the different types of ways requests can be structured and nested.

The example we chose to expand was one of the Filibuster corpus’ cinema examples. It consists of four services: users, bookings, showtimes, and movies. These services allow the user to retrieve user information, book movies, retrieve showtime information, and perform other actions one might expect from a cinema site.

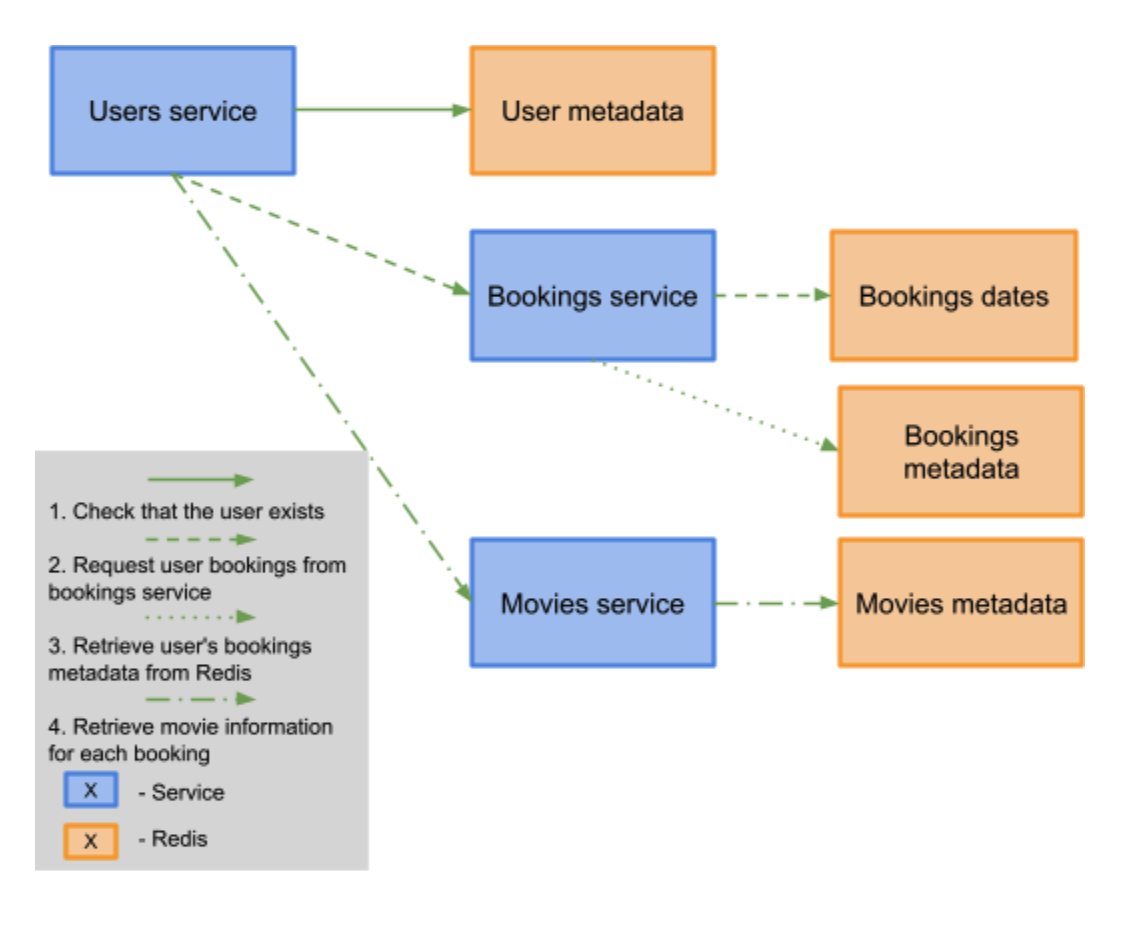

While this application exposes several different REST APIs, one important API allows users to retrieve their movie bookings. Starting with a request from the client to the users service, the application makes several GET requests to retrieve their bookings, as shown by the diagram below:

Retrieve Bookings

First, the users service makes a call to Redis to check if the username exists in the database. If the user does not exist, then the users service will return a 404 Not Found. If the Redis call returns a successful response, then the users service will contact the bookings service and request the data associated with the given username.

Once the bookings service receives this GET request, it takes the following steps:

- Check that the username exists in the bookings database via Redis call.

- If the username doesn’t exist, then the bookings service will return a 404.

a. When the users service receives this response, it returns a 404 back to the user. - If this call is successful, retrieve the dates on which the user has booked a movie from Redis.

- For each booking date for that particular user, retrieve the movie identifiers. The movie identifiers are unique to each movie.

- Return a JSON object containing the movie identifiers associated with each booking date for the user.

After the users service has received a response from the bookings service, it contacts the movies service and retrieves the movie data associated with each movie identifier. Then, the movies service retrieves the movie data from Redis and returns the data to the users service, which then returns the data to the user.

Testing The Bookings API

To test this endpoint, we make a request to the users service that will retrieve a particular user’s bookings, which corresponds to the endpoint users/{username}/bookings.

In our test, we look for the bookings associated with chris_rivers, so we make a call to the endpoint users/chris_rivers/bookings.

We start with the basic functional test behavior that would exist prior to our adaptation for HTTP RPC fault injection.

Our test asserts that if the response code from this call is 200 OK, which indicates success, the data returned matches the data associated with the chris_rivers user.

To handle the cases where Filibuster has injected faults for the HTTP RPCs, we add conditional code to account for behavior under failure.

In the case where an RPC fails, our test asks Filibuster to verify whether it injected a fault, i.e., that the fault was intentional — this is done using the was_fault_injected() conditional. Our test asserts that if the RPC failed, Filibuster did actually inject a fault and the HTTP status matches the expected status when the call fails.

In this case, since the only errors we expect are a 404 Not Found or a 503 Service Unavailable, we assert that the status code must be 404 or 503.

We excerpt the test below:

bookings_endpoint = "{}/users/{}/bookings".format(helper.get_service_url('users'), 'chris_rivers')

users_bookings = requests.get(bookings_endpoint, timeout=helper.get_timeout('bookings'))

if users_bookings.status_code == 200:

assert users_bookings.json() == {'20151201': [{'rating': '8.8','title': 'Creed','uri': '/movies/267eedb8-0f5d-42d5-8f43-72426b9fb3e6'}]}

else:

assert was_fault_injected() and users_bookings.status_code in [404, 503]

To run Filibuster with our functional test, we can run the following command which will inject HTTP exceptions at each RPC call site.

filibuster --functional-test ./functional/test_user_bookings.py

Now, let’s test our application’s resilience to Redis failures.

Testing Calls to Redis

For Filibuster to inject faults at each Redis call site, we need to expand the list of faults that Filibuster uses for fault injection.

To do that, we modify Filibuster to inject connection errors, timeout errors, and response errors for calls that are made using the execute_command primitive.

Below is the additional Filibuster configuration containing these new faults:

"python.redis": {

"pattern": "redis\\.execute\\_command",

"exceptions": [

{

"name": "redis.exceptions.ConnectionError"

},

{

"name": "redis.exceptions.TimeoutError"

},

{

"name": "redis.exceptions.ResponseError"

}

]

}

Once we modify the list of faults that Filibuster uses for fault injection to include Redis, we can rerun our Filibuster command from before. Filibuster will systematically inject these Redis errors (along with the HTTP RPC faults) one by one, then in combinations, while repeatedly executing our functional test.

For example, in one test, Filibuster might inject a ConnectionError exception when the user retrieves the user metadata.

In another test, it may try to inject a TimeoutError exception when the bookings service retrieves booking dates and a ResponseError exception when the bookings services retrieves movie identifiers.

Filibuster will test all possible combinations of these errors in the different services until the fault space is exhausted.

Because the application does not handle any Redis exceptions, the application returns a 500 Internal Service Error. Instead of altering our functional test to allow for a 500 Internal Server Error, we want the service to return a 424 Failed Dependency if one of the dependencies, in this case Redis, is down.

try:

booking_ids = r.hgetall(user_id)

except redis.exceptions.RedisError as e:

print(e)

raise FailedDependency

Before, our test asserted that if the call failed, then the fault was intentional and the HTTP status matched the expected status. We change our test to expect a 424 response code in addition to a 404 error:

else:

assert was_fault_injected() and users_bookings.status_code in [404, 503, 424]

When the test execution fails, Filibuster generates a counterexample file that contains the specific fault(s) that caused the failure. Counterexamples allow the developer to rerun the specific generated (and failed) test and attach an interactive debugger. To use the counterexample to rerun a failed test, we supply it to the Filibuster command as follows:

filibuster --functional-test ./functional/test_user_bookings.py --counterexample-file counterexample.json

Once run, we see that the test now passes the previously failing test.

Therefore, we know that we have fixed this particular bug.

Finally, we can run Filibuster again and test for the whole default set of failures as well:

filibuster --functional-test ./functional/test_user_bookings.py

From our output, reproduced below, we can now see that everything passes.

[FILIBUSTER] [INFO]: Number of tests attempted: 52

[FILIBUSTER] [INFO]: Number of test executions ran: 52

[FILIBUSTER] [INFO]: Test executions pruned with only dynamic pruning: 21

[FILIBUSTER] [INFO]: Total tests: 73

[FILIBUSTER] [INFO]:

[FILIBUSTER] [INFO]: Time elapsed: 9.103456020355225 seconds.

Because Filibuster exhausts the failure space and everything now passes, we know that the application behaves exactly as specified by the functional test. Specifically, we know that the endpoint returns the correct data (in the case of a 200 OK response), or that its failure behavior matches the expected behavior (i.e. a 404, 503, or 424 response). In either case, because we have correctly handled any exceptions that may arise, we can verify that the application does not fail in unexpected ways when one of the services it depends on fails.

For this example, Filibuster ran 73 tests: 72 generated tests from the original test plus the original test itself. Without Filibuster, developers would have to write 72 tests manually in order to exhaust the fault space. However, Filibuster does this automatically. In doing so, it is able to prune 19 redundant tests (for more information on how this is done, see this post). It completes this entire process in only 9.1 seconds, allowing developers to test their code quickly.

Conclusions and Future Work

When we started this work, we had two questions:

- Can Filibuster be expanded to support database calls?

- How would this new support for database calls change the way the Filibuster tool interacts with microservice applications?

After building our Redis prototype, we can now begin to answer them.

As demonstrated by the example above, we are, for the most part, able to extend Filibuster to accommodate database calls. While our first prototype of this in Filibuster uses Python’s Redis library, our early results indicate that extending Filibuster to more languages and database implementations is a promising direction for future work. Thus, the answer to our first question is yes, we can expand Filibuster to support database calls.

While this prototype demonstrated that many of the design decisions made in Filibuster itself were correct, we also discovered several ways where we believe we need to modify Filibuster to support further, in-depth testing of database clients. One specific way is simulating different types of failures – not spurious faults – in Redis, based on the Redis method that is being called. We demonstrate this using an example below.

With respect to HTTP RPCs, whenever we want to inject a failure that doesn’t cause an exception, we can simply return an HTTP response back to the caller containing the associated status code to indicate failure. This is similar to GRPC as well: a single GRPC return type is provided and a status field set indicating the type of failure. However, with Redis, different return types are used depending on the Redis API used.

For example, the hget method, which gets the value of a hash field, may return a different type of value than the sismember method, which determines whether a given value is a member of a set.

The hget method can return strings, integers, or None, whereas the sismember method returns only 0 or 1 depending on whether the value is or is not a member of a set.

If the user calls redis.hget(id), and the id does not exist in the database, then Redis will simply return None.

However, if the user had instead called redis.sismember(set_name, id) for an id that didn’t exist, then the response would be 0 (i.e., False).

Since what constitutes a failed response varies based on the Redis method called, we are exploring different ways Filibuster can simulate those failures.

In doing so, we can expand the way the Filibuster tool interacts with microservice applications.

Through this work, we have extended Filibuster to support Python’s Redis library. In doing so, we have learned that it is feasible for Filibuster to be successfully extended to more languages and database implementations. At the same time, we raised interesting new questions and have found new directions for the Filibuster tool to grow in.