Reflecting on 10 years of Blogging, Research, and a (very) long Ph.D.

June 03, 2023 marks 10 years since I started my blog, and, it’s sort of mind blowing, honestly.

When I go back and look at my old posts on my blog, well, it’s quite fitting that my first blog post was on fault injection and fault tolerance, because that’s the topic that ultimately became my Ph.D. research, of which I’ve been focused on since 2015… but really since 2018.

Since creation of this blog, I’ve been lucky to have many of these posts make the front page of Hacker News and Lobsters, which at minimum, encouraged me to keep going. This visibility has been instrumental to my career, despite the (sometimes) negative comments, but, wow… what a ride it has been.

But, perhaps what is most interesting to me, is that the genesis of this blog was at the exact moment that I first ventured into research. When I started my dream in 2013 — when I started this blog sitting in a wicker chair in the corner of the living room of my close friend Greg in San Francisco with a re-run of Friends on in the background — my goal was to work at Microsoft Research. When I started my Ph.D. in 2015, my goal was to be a professor in France. In 2018, I thought I might be a teaching professor in the US.

Things change: shit, it’s been only 10 years!

In some ways, it is fitting that this 10 year milestone corresponds with the year that I will (hopefully) defend my Ph.D. at Carnegie Mellon University: if not this year, early next year at the latest.

The Inticement of Research

I started this blog as a Software Engineer at Basho Technologies, a now-defunct distributed systems company that was primarily focused on writing a fault-tolerant, highly scalable distributed database in Erlang. At the time, I was a JavaScript developer building the UX for Basho’s distributed database, Riak. I did not know Erlang — only enough to maintain a job where I had to produce JSON from Erlang to build the UX for Riak — and, I barely knew JavaScript. However, I was not new to programming as I had been a software engineer, systems engineer, and even a software engineering manager for many years before coming to Basho. But, I ended up here because when I became a manager, I decided it wasn’t for me and I wanted to be a programmer again and restarted my career from the beginning as a junior developer and working my way back up. I slowly moved from being primarily a TCL programmer for web applications — ArsDigita crew represent! — to manager, and then back down again to a Ruby programmer, and up again, to finally, a JavaScript developer at Basho.

I really knew nothing of distributed systems at the time. I didn’t read my first distributed systems paper until 2012.

However, by 2013, I was very interested in both Erlang and distributed systems and by merely playing around in my spare time, had wandered into the area of fault injection and fault tolerance. My first and second blog posts were specifically on this very topic. I did not know at all what I was doing – as I’ve said numerous times in the past, writing is a way for me to understand something and I write specifically to help clarify my own thinking on a topic. In short, I found something that was interesting, started writing about it, and then wrote code to figure it out.

In 2013, I decided I wanted to start grad school to really learn about a programming area, as as I was living in Rhode Island, reached out to Brown University, where some members of my family had attended. They wanted nothing to do with me for several reasons. First, I didn’t have a degree in CS, because I got one in IT part-time at Northeastern University after getting an associate’s degree at the Community College of Rhode Island. Second, I had no research experience. I was told “no research potential” by one prominant faulty member, which reminded me of Zappa’s infamous “no commercial potential” response. Finally, after reaching out to a professor at Brown based on a paper he published that I had reimplemented for fun – and once I told him that I programmed Erlang in industry — he gave me permission to enroll in courses as a “special student.”

A “special student” means a couple different things. First, that you have to carry around a bright pink slip to all of your courses on the first day of classes begging to be admitted to the professor of the class, as you are not a degree student. Second, that you have to pay your own way — at the time, $6k a course. I doubled down, got my slips signed, and blew (part of) a family inheritance to take my courses. I took a database seminar (not knowing what a seminar was) and a programming language course with Coq (not knowing what Coq or programming languages really were, outside of writing computer programs.) I got lucky in that both of my course projects were decent. In fact, I dicussed one at RICON, the distributed systems conference in 2013: my work on writing CRDT proofs — really, really, awful trivial proofs, but the first person to actually try writing proofs for CRDTs — and it seemingly got me noticed by many people in the field. I was in!

In 2014, Basho established a research consortium with a number of universities in the European Union to work on the development of CRDTs for use inside of Riak. I wasn’t invited, but several of my friends/colleagues were. One January evening, lying in bed with the flu in my parents spare bedroom a few days after Christmas, I asked a colleague where they were going in Europe. When I found out, I applied for a Delta credit card, was accepted, bought a flight, asked my colleague if I could room with him for the event, booked an AirBnb in the city, and just showed up there myself and said “hey, I’m with Basho.” From then on, I became involed in the research project in several different capactities over time, travelling back and forth to Europe for the company.

I got to work on various CRDT related research projects, ultimately building a new programming model and (partially) overseeing the development of a database called Floppystore, which became a database called Antidote DB. I visited Rovio and a number of our other clients in various countries. I gave talks at a bunch of conferences, collaborated with many different folks across organization and companies, and finally dissapointed with my job during the decline of Basho — I was working on testing, which ultimately became my Ph.D. — decided to quit my job and do a Ph.D. in CRDTs once I published my first research paper.

At that point, it was on. I literally donated all of my belongings that I had accumulated at 30 years old to charity, and with only a single suitcase and carry-on, moved to San Francisco for several months to work a contract job on formal verification — which I knew nothing about — and then when finished with that contract, proceeded with my move to Europe for my Ph.D.

Things were looking up.

The First Attempt at Research

Living in Europe had always been a dream of mine, ever since spending much of my Information Technology degree at Northeastern watching French film, reading French literature, and having spent much time in Paris with a former romatic partner of mine who was born there. I loved the culture, the city, and fully embraced the lifestyle: it honestly felt like an absolute dream. There is no place else I would ever want to spend the rest of my life.

At the start, my Ph.D., was nothing short of wonderful experiences. I spent weekends in various different cities, traveled to 20+ different universities giving talks on CRDTs, Erlang, and distributed systems, and met (and then collaborated with) some of the most friendly and welcomining people that I will call friends for the rest of my life.

However, my research progress was awful. This wasn’t to say that I wasn’t doing research: I was writing code, building prototypes, showing off example applications, performing evaluations, etc. In fact, when we finally presented our project results, I was one of the key presenters at our project review meeting in Brussels for the European Commission. We had built a lot of software and it worked well, and it worked well at scale. But, from the point of view of doing a Ph.D., I just felt stuck. Perhaps my heart wasn’t in CRDTs anymore: as it would seem, it wasn’t and I completely abandoned it as a research topic.

Thankfully, I got an internship at Microsoft Research in Redmond, primarily thanks to my previous work on Erlang and actor systems. This work, over the summer, is work that ultimately lead to the transactional semantics in Orleans, but it was a rough start. When arriving at Microsoft, I didn’t know what to do. I wasn’t used to the culture of extremely, minimal supervision and spent the first month just drinking coffee and reading papers that I thought were relevant. I didn’t know transactions, I didn’t know how they worked, I didn’t know the names of all of the properties of isolation or whatever.

Phil Bernstein, however, was an incredible mentor. He pointed me in the directions of the right papers, gave me his own copy of his book on transactions, and upon going home each night, I would sit and read as much as I could. I started by benchmarking transactions, and each day as I learned more and more, I got better at figuring out how things worked, what each thing was called, and what each thing meant. I absorbed every paper Phil even mentioned in passing, and tried to learn as much as I could. I thought things were looking up and I was starting to feel more at home in my own skin.

However, I was sick every single day of the week. Horribly sick, every morning and spending each evening sick.

I thought at first it was stress, but each day it became increasingly worse: I just couldn’t stay out of the bathroom. Finally, after visiting several doctors and performing a number of experiments myself each day with what I ate, I figured it out. I could no longer eat bread.

I lived in Europe, and I couldn’t eat bread anymore without getting horribly sick.

When my internship ended, it was time to return to Europe, but a condition of my Ph.D. grant (Erasmus) was that I had to switch universities every year and have two different Ph.D. advisors, so I returned to Belgium and after a few months headed off to Lisbon. In Lisbon, I fared less well: I knew French, but didn’t know Portuguese, and I also had to communicate to everyone that I couldn’t have dairy or gluten anymore. Complicating this, my Ph.D. advisor in Lisbon wanted me to work on a different project than my Ph.D. advisor in Belgium did. I was lost, between conflicting responsibilities from different advisors, while sick, in a place where I didn’t speak the language. I hobbled along for almost a year — completely lost, depressed, sick, alone, and otherwise miserable — and was lucky enough to be invited back to Microsoft Research.

At Microsoft Research that year, I was mentored by Sebastian Burckhardt, who was involved in our previous project as well and who has since become a close friend of mine. Sebastian, who I had known for a long time because he was extremely critical of my CRDT work years earlier, was a a fantastic mentor and great person, who helped me to grow in a number of ways. Here, we took the ideas we developed in Orleans and built the first version of stateful serverless, which we open sourced at the time, and became Durable Entities on Azure. Not only this, but Sebastian introduced me to Jonathan Goldstein at Microsoft, where I got to work with cutting edge database systems and help define part of that systems API. I was eating gluten-free, things were great, and I was flying high.

But, on return to Europe, I was miserable. Back in the same place, with no direction, no clear end to the Ph.D., despite being in year 3 of my 3 year funding, and sick once again from being able to properly control my diet in the foreign land. I dabbled with starting a company in France based on our previous work – we met with several VC funds which didn’t pan out. Instead, I spent a few months there, and upon returning to the United States, quit my Ph.D. via email from a bar (Miracle of Science, it’s you!) on Massachusetts Avenue in Cambridge, Massachusetts while watching a Boston Celtics game on the television and told my collaborators that I would not be starting a company in France. I left all of my belongings, outside of what I could carry in a suitcase, in my apartment in Portugal, which my landlord claimed as payment for the security deposit. I was lucky enough, that I had already accepted an offer for a return to Microsoft Research that summer, depsite having just quit my Ph.D.

Upon return to Microsoft, things were great. I corrected my diet, was living a place where I could control cross-contimation by not sharing a kitchen with other students, had a car to grocery shop, and was doing quite well. However, from the research perspective, I was making less progress. I was working on effects systems and capturing nondeterminism and built two different versions of the system – one research with strong guarantees and one practical with fewer guranteees, which both worked — but no one seemed particularily impressed. I felt like I was doing very pratical useful work, but my research presentations were under-attended and no one seemed to really care. I still felt lost.

Not knowing what to do with what remained of my (non-existent) career, I was lucky enough to get enrolled at Northeastern University as Ph.D. student thanks to my future Ph.D. advisor Heather Miller — who I had known from many moons ago when she was a grad student and I was an industry participant at a PL summer school in Oregon, and who I organized the Curry On conferences at ECOOP with — and who I had been working with on and off on projects while I was untethered in Boston since quitting, to promising success. However, by the time I finished up at Microsoft, she had left Northeastern and was on her way to Pittsburgh, PA, at Carnegie Mellon University. Carnegie Mellon was a bit of an upgrade from a smaller European university in Belgium and, definitely so for someone who Brown University considered had “no research potential.” And, it showed.

My first semester, I failed out of one of my courses and landed in the hospital for a full week: overwork, stress, and an improper diet had caused my pancreas to go into overdrive and I was at risk for pancreas failure. However, with some rest and a slight course correction at CMU, things got back to normal and soon enough I was passing courses and doing good research. I ended up taking my work on building an evaluation framework for our SyncFree work three years prior and turning it into a top-tier conference paper at USENIX ATC my first year at CMU with the help of Heather. Things were looking up, but I had absolutely no direction how to proceed. This was soon to change.

The Redemption

In late 2018, I started playing around with the idea of fault injection. My previous paper, Partisan, had been focused on building a distributed runtime: my thinking was that if you control the runtime, you can inject faults any of the communication that is performed by the runtime. It seemed the clear natural extension of the Partisan work, and would be a good second (of 3) piece of my Ph.D. thesis.

So, to demonstrate, I built several example applications, adapted blockchain applications and distributed databases, all to use this fault injection framework. I even implemented 3 different transaction protocols based on my previous work at Microsoft Rsearch. However, my work was just too simplistic to find bugs. I just couldn’t compete with any technique that used model checking, with advanced heuristics, and the very same year that I tried to publish my work — which was rejected — another researcher came out with something far more advanced for Erlang that found significantly more bugs.

But, this fault injection idea stuck with me and I kept on working it. Instead, I thought, rather than try to target the identification of concurrency bugs where so many existing researchers are focused, why not try to target microservice bugs, where no one is working and publishing, instead?

I decided to write proposal for this work and other work that fit into my broad vision of how microservice software should be developed.

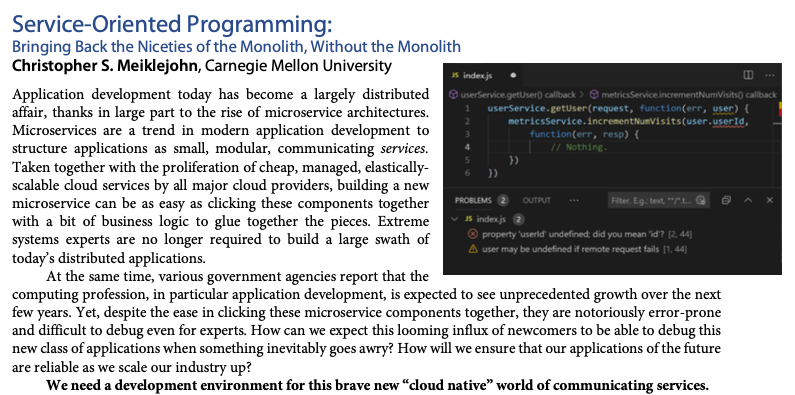

I wrote a Microsoft Research Fellowship Proposal in early 2019 that started like the following:

❌ Rejected.

I was dissappointed, but I was lucky enough to get an internship at Amazon in Automated Reasoning working on S3 to do concurrency testing and model checking that same week, so it mitigated the blow of yet (another of many) rejection.

However, once returning from my Amazon internship, I was still left in a place of uncertainty with my own work: I should have been done with my Ph.D. already!

It wasn’t until I randomly took a program analysis course that I realized my true love of programming is reasoning about, and verifying, program correctness. This was, without a doubt, the one course I took that changed the course of my Ph.D.

So, I decided to reimplement my fault injection strategy in Python for use on microservice applications written in Python (this was done based on a potential user, who never materialized) and was lucky enough to also have students reach out to help me as part of an undergraduate research inititive while I was doing the work. I started the work late ‘19 and the students helped out in late ‘20: we submitted early ‘21 for the May deadline of SoCC ‘21.

Our first paper on what is currently called Filibuster got in, first shot.

In my perpsective, this is when my Ph.D. actually started: the first Filibuster paper at SoCC ‘21.

From this point forward, it’s been a whirlwind experience, which I’ve blogged about in detail:

- Filibuster’s results led to some industry adoption and sponsorship of future development;

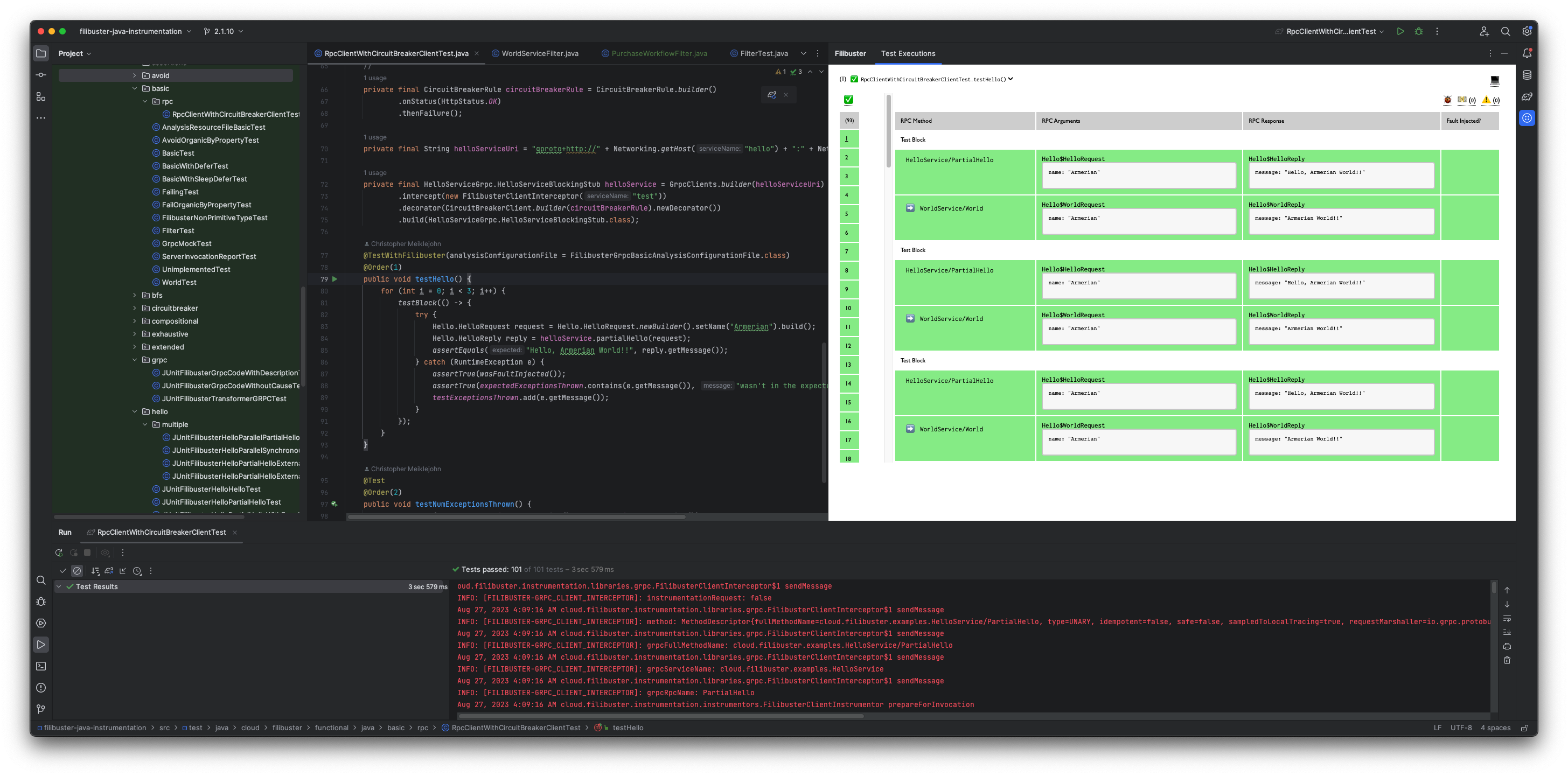

- Filibuster was completely reimplemented in Java and adapted to handle GRPC;

- Filibuster’s work led to a joint published paper at SoCC ‘22 with DoorDash on circuit breaker usage for fault tolerance in ‘22;

- Filibuster now provides an integrated development experience in Java with JUnit integration and IntelliJ plugin integration in ‘23;

- Filibuster has been the focus of multiple students undergraduate research projects;

- Filibuster is the subject of an upcoming master’s thesis on fault injection for database calls; and

- developers are actually starting to use Filibuster.

Today, Filibuster looks like this:

It’s not quite the same as my MSR proposal — which was quite aspirational and covered type checking, fault injection and more — but what we have is significantly more focused, as necessary for a Ph.D., and works on real application code and finds real bugs through it’s integrated fault injection development experience.

It’s come a long way and I have to thank my colleagues at CMU, colleagues at DoorDash, and my advisor Heather for the motivation and support that was required to push it forward.

Epilogue

I think a lot about whether my Ph.D. experience was worth it or not as it slowly comes to a close.

First, I did not work on exactly what I thought I would, and therefore my Ph.D. ended up being quite different than what I thought my Ph.D would be.

- I started in CRDTs; I left that area and moved to program analysis and testing.

- This made sense for me, but only in retrospect: I had done testing for years before moving to Basho and then did distributed systems testing at Basho.

- Testing was a thing I was good at — and as my initial blog post indicates, and it was the motivation for my initial blog post 10 years ago — before I even started a Ph.D.

So, for me, it makes sense, but it was not the thing I signed up to do and wasn’t what I set out to do. This wasn’t a dealbreaker for me — I feel like I discovered my true calling — but, it’s something that happend.

When it comes to the negatives of the Ph.D., they are quite clear:

- I literally started my life over with nothing but a suitcase upon returning to United States in Pittsbugh, at 36 years old.

- I was a Senior Software Engineer in 2015 and forfeitted a potentially (lucrative) tech salary for almost 8 years to live as a grad student. Given this — and if I ever wanted to be a professor full-time that lived in a city — it’s highly unlikely I’ll ever be able to make any substantial purchases in my life: for example, real estate.

- The stress during my Ph.D. was so high, that I developed an autoimmune disorder (e.g., celiac disease, lactose intolerance, IBS) that severly limits my ability to travel.

The impact of these negatives on my goals are quite clear:

- I’ve given up my dreams of being a professor in France: it’s just too late with too many restrictions.

- I no longer travel to conferences and visit universities, the things that I enjoyed most as a researcher.

In contrast, the positives:

- I was able to travel the world for a brief period as a researcher with minimal responsibility, which resulted in some great experiences, great friendships, and broadening of the mind.

- Most importantly, I got to spent several years of my life working on a problem that I thought was extremely interesting and, which for a short-time, was my entire world. I examined the problem completely, and contributed what I thought was a solution to it. It was all me, and it’s something I can always look back on and be proud of. Whether or not it’s forgoteen is up to time, but I know that I did everything that I could to investigate the problem.

What a fucking journey, that’s all I can say.

"...waiting for the time when I can finally say, this has all been wonderful, but now I'm on my way..."