I Built a Social App in a Week with Claude Code

I spent the better part of a week building a social app with Anthropic’s Claude Code. Most of that work happened late at night, sometimes past 2am, iterating on features until I had something worth sharing with friends.

Anthropic generates a weekly insights report for Claude Code users. Mine told an interesting story: 384 messages, 27 sessions, 168 files touched, six days. A median response time of 29 seconds — I was barely reading the output before firing back. They described my style as “reactive and corrective rather than spec-driven,” which is accurate. I was moving fast, fixing things as they broke, and learning what worked along the way.

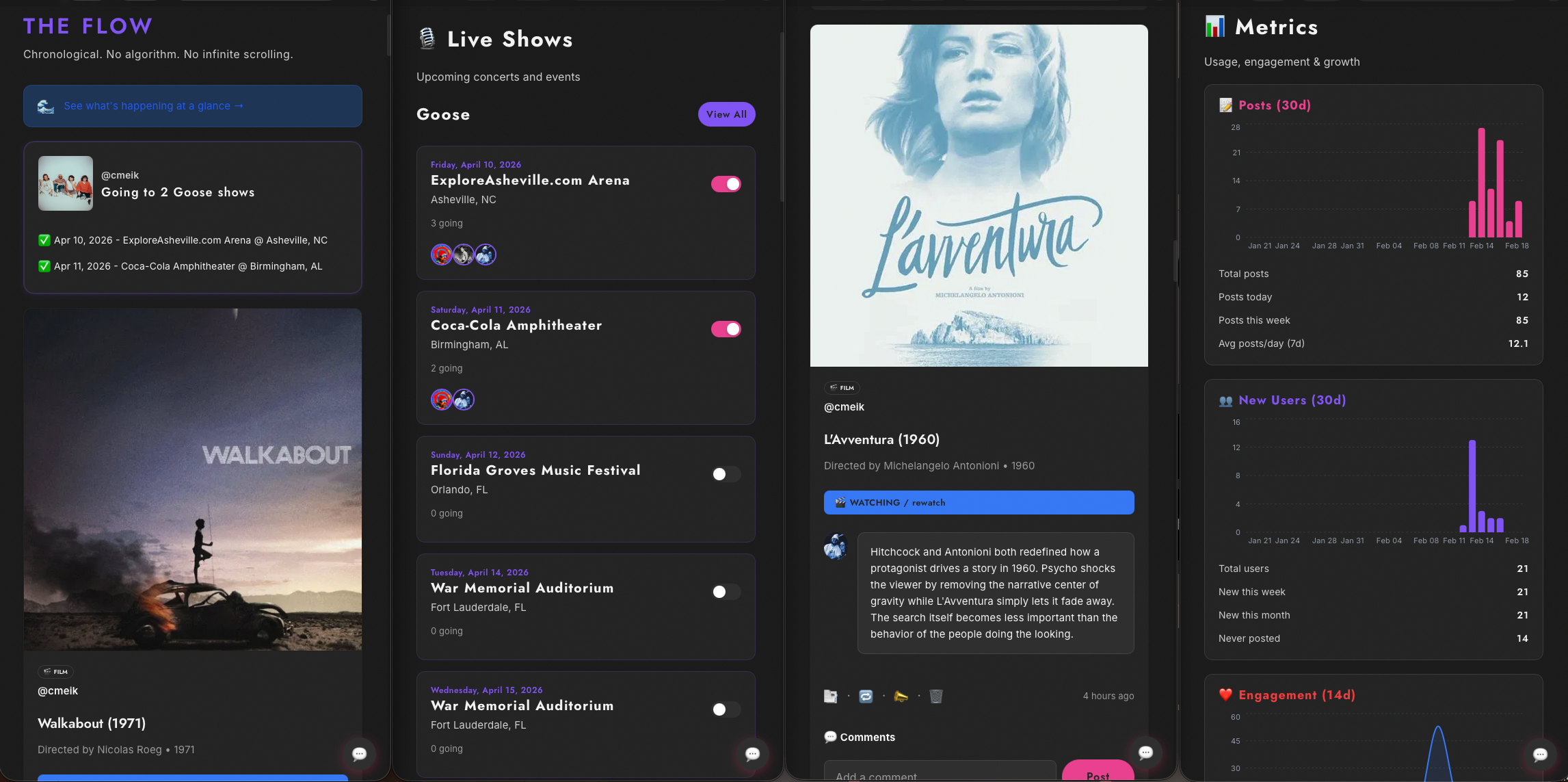

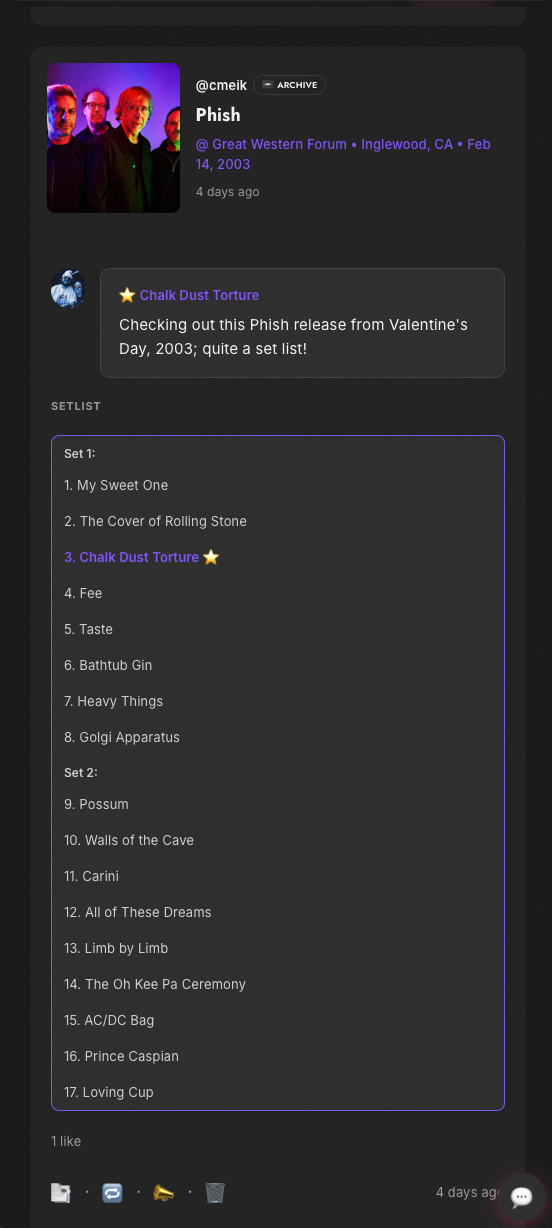

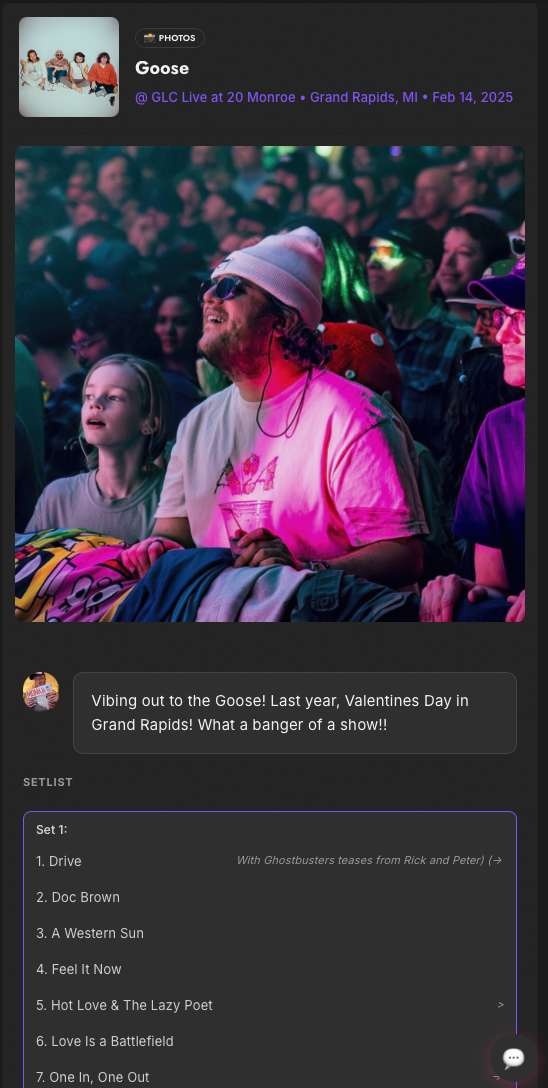

What I was building: a private social app for my close-knit group of friends. We share live recordings of bands — Phish, Grateful Dead, that world — favorite films, books, and which upcoming shows we plan to catch this summer. Think a tiny, invite-only corner of the internet for people who care deeply about live music and want somewhere to talk about it with people they actually know. Live chat between people couch-touring and people in the pit is coming next.

The app is live. My friends are using it. It runs on Go with a server-driven UI architecture, and it ships as native iOS and Android apps. I built all of it in a week with Claude Code, and I want to tell you what that actually felt like.

The entire first version was built at night, in bed, on an 11” iPad, using the Claude Code app connected to an empty GitHub repo. I didn’t touch a computer. Within a few hours I had a working app — login, a feed, posting — deployed and running on Railway. From there the scope crept in the right direction: Spotify integration so you could search and attach albums and tracks directly, setlist.fm integration to pull real show data — venues, dates, and actual setlists as they’re posted after each night — and let people mark which dates they were attending. The bones were there fast; making it feel like something worth actually using took longer. Claude scaffolded the backend, wired up the database, built the frontend, and I shipped it without leaving bed. It wasn’t until late in the second day that I moved to a laptop, mostly because the screen real estate was starting to feel limiting. The code itself didn’t care.

The day I invited most of my friends, a database migration corrupted production timestamp data.

The migration modified column types in a running database. Timestamps encode timezone assumptions at the type level — change them mid-flight and the data doesn’t migrate, it breaks. The feed went down. I asked Claude to fix it. Each fix made things worse: wrong column names, broken SQL syntax, incorrect timezone arithmetic, until finally an overwrite ran that couldn’t be undone. The Anthropic report summarized it as “Claude’s database migrations went full disaster movie — each fix spawned a new production incident, permanently destroying timestamp data.” That’s accurate. Some of that data is simply gone.

I spent years working on databases. I knew exactly what was happening and why it was catastrophic. I let it happen anyway because I was vibe coding, hands off the wheel, just watching Claude drive.

The timestamp disaster was the worst single incident, but the pattern underneath it showed up constantly: Claude moving confidently in the wrong direction, and me not stopping it soon enough. Push notification debugging is another example. Missing APNs tokens sent Claude deep into provisioning profiles, certificates, entitlements — a long, plausible-looking path that turned out to be completely wrong. The actual problem was missing AppDelegate methods in code Claude itself had written earlier. The report counted 30 instances of wrong-approach debugging across the project. That’s a lot of time watching a very capable thing solve the wrong problem.

The server restart issue was more mundane but somehow more maddening for it. After any change to Go code, you have to restart the backend for the changes to take effect — compiled language, nothing exotic. Claude kept forgetting. I kept seeing no changes, assuming something was broken, investigating, finding nothing, eventually realizing the old process was still running. This happened across four or more sessions before I wrote a rule explicit enough that it actually stuck. pkill was the culprit — it fails silently, leaving the old process alive. The fix was lsof to find the PID, kill -9 on that specific process, wait, restart, verify. A procedure that takes thirty seconds and has to be written down or it doesn’t happen.

What got built, despite all of this, is genuinely surprising to me.

A full server-driven UI migration — the backend sends the entire interface as JSON, the React frontend just renders it, no hardcoded pages. This one has a story. I’d instructed Claude from the start to build an SDUI app, but most of the early code landed in React anyway. The upside was that the initial pages were genuinely pretty — Claude has good taste in React UI — and I loved how they looked. The downside was that enabling a proper mobile strategy required full SDUI, which meant migrating every page individually, each one needing to be restyled from scratch. That work took real time.

The migration also exposed a pattern that would recur throughout the project: Claude claiming victory prematurely. Buttons that didn’t work. Frontend calls to backend routes that didn’t exist — phantom APIs, confidently wired up. Forms that submitted successfully from the UI while silently dropping half their parameters on the way to the backend. Claude would build a form, build an API endpoint, connect them, and declare the feature done. The form would submit. The endpoint would return 200. Nothing would actually be saved.

I eventually had to encode explicit rules: when you add a new backend API, test it with curl before touching the frontend. When you wire up a frontend call, verify the route actually exists. When a form submits, confirm every parameter arrives at the backend. The quality improved significantly once those guardrails were in writing.

iOS and Android apps, both in TestFlight and ready for Android testing within the same week. End-to-end push notifications wired to every interaction. An AI-powered feature that surfaces what your friends are collectively into right now. An invite management system, automated build scripts, 107 database migrations, user engagement charts, a changelog that notifies users when something new ships.

Claude’s ability to hold a large multi-file change in mind — a database migration, a new API handler, a frontend component, and a mobile layout fix, all in one coherent session — is where it earns everything. When the scope is clear and the pattern is known, it moves at a speed that doesn’t feel real.

Only 2 of my 27 sessions fully achieved what I set out to do. That number sounds damning until you consider that 27 sessions in six days shipped something real that people are using. The sessions that failed were almost always the same shape: open-ended, no clear stopping point, debugging something visual or stateful where Claude had no feedback loop and I had too much patience for wrong approaches. The sessions that worked were tight — one known thing, done correctly, then stop.

The insights report also came with recommendations, and they’re worth passing on.

The biggest one: hooks. Claude Code supports post-edit hooks — shell commands that fire automatically after files are changed. The report suggested wiring one up to restart the Go backend after any .go file edit, which would have eliminated the single most recurring waste of time in the entire project. I haven’t set it up yet. I’m going to.

The report also suggested adding explicit guardrails to CLAUDE.md — the project instruction file Claude reads at the start of every session. Things like: after any backend code change, always restart the server before testing. Never run migrations or deploy fixes without explicit user approval. When the user tells you a layer is working, stop investigating that layer. Limit yourself to two attempts at a single approach — if it hasn’t worked twice, step back and explain what you’ve learned before trying again. Most of these I’d arrived at the hard way over the course of the week. Having them written down from the start would have saved days.

The other recommendation was about session discipline. Five of my sessions were completely lost to context limits — the conversation grew too long, and when I tried to recover with /compact, it just returned “failed to compact” and left me stranded mid-task with no way forward except closing Claude and starting over from scratch. Losing context mid-session, mid-thought, mid-fix, with no handoff and no summary, is a particular kind of frustrating. The fix is obvious in retrospect: end each session at a natural stopping point, write a brief summary of state, start fresh. The sessions where I shipped something were the tight ones. I kept ignoring that signal.

The report called my style “ambitious” and noted I “tolerate high friction from repeated wrong approaches.” I’d put it differently: I was building something I actually cared about, for people I actually know, and the deadline was real. Spring tour is the test. Summer tour is the goal. That changes your relationship to the friction.

You’re not writing code with Claude Code. You’re steering. The gap between those two things is where all the frustration lives, and also where all the speed comes from. When you accept that you’re the judgment layer — deciding when to redirect, when to stop, when a fix is making things worse — the tool becomes something genuinely extraordinary.

Spring tour is coming. The app is ready.

Postscript: while writing this blog post, the same pattern bit me again. The app was deploying fine on Railway with a simple nixpacks build. While fixing an unrelated feature, I added a healthcheck to the config as a drive-by change — unnecessary, but it seemed harmless. Later, switching to a Dockerfile build to bake in an environment variable caused the build to take longer than nixpacks, so the healthcheck started timing out before the service was ready. Deployments failed. Rather than identifying the healthcheck as the culprit, five successive commits changed the port, the builder, the start command, and the Dockerfile in various combinations. None of it worked, because the real problem was never diagnosed. The entire chain of failures traced back to one unnecessary line added while working on something else entirely. Some things don’t change.