Applied Monotonicity: A Brief History of CRDTs in Riak

Riak

Around 2013, Riak was at the forefront of Conflict-Free Replicated Data Type (CRDT) development with the engineers at Basho Technologies working hard to integrate efficient, usable CRDTs from the academic literature. Basho had a collaboration with the researchers in the SyncFree Consortium, authors of the original CRDT work and actively researching new CRDT designs and their applicability in industry use cases presented by both Rovio Entertainment (creator of Angry Birds, participant in the SyncFree Consortium) and Riot Games (creator of League of Legends, long time Riak user.) On the Basho side driving the effort was Russell Brown, working with Sean Cribbs, Sam Elliott and myself.

At the time, designs for CRDT-based dictionaries did not exist, and the designs used for sets were extremely expensive or prohibitive for use in real applications. For instance, the Grow-Only Set did not allow users to remove elements once added; the 2-Phase Set did not allow users to remove elements more than once; and, the Observed-Remove Set, while allowing arbitrary remove and addition operations, had a space complexity of O(n), not on the elements in the set, but the number of operations ever issued against the set, because of the required bookkeeping. This meant that a set could require large storage for a set that, at an arbitrary point, may contain no elements.

Inspired by previous work (Bieniusa et al. 2012) on optimizing CRDT set representations for operation-based CRDTs – Riak needed state-based CRDTs due to it’s lack of causal delivery and anti-entropy replica repair mechanism – Russell arrived at a design for an optimized set representation that was dubbed the Observed-Remove Set Without Tombstones. This data structure only required O(n) space where n was the number of elements currently in the set, along with a fixed overhead O(n) integer version vector for the number of participants in the cluster working with the set.

This design was integrated in Riak that year, announced and discussed at the RICON West conference in 2013 and served as the basis of the CRDT based dictionary designed by Basho. This design lead to an abstract (Brown et al. 2014) on the dictionary presented at the first PaPEC Workshop (colocated at EuroSys 2013, now the PaPoC Workshop) and has been cited over 35 times – quite a large number of citations for an abstract that contains no implementation details – by systems that leverage or are inspired by the design. Shortly after, a similar design was formalized (Almeida, Shoker, and Baquero 2015) by our colleagues in Portugal under the name the Add-Wins Set. This set design went on to be quite influential, with it being used in both Phoenix Presence (for the Elixir programming language) and Akka (for the Scala programming language.)

The Observed-Remove Set

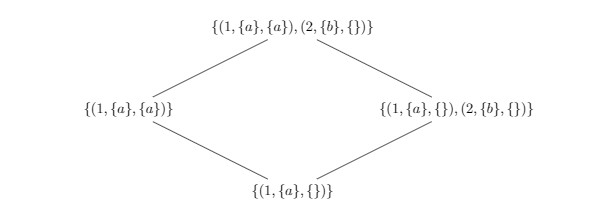

To discuss the design of the Observed-Remove Set Without Tombstones, let us first look at how the Observed-Remove Set works. For each element we insert into the set, we associate it with a unique token, and then when removing an element, we mark the add tokens that we observed as removed. When two replicas each perform different operations, we take the union of the add token set and remove tokens set.

We start with a set where the element 1 exists in the set because it was added with logical token a. We then diverge by having two replicas perform different updates: on the left, the element 1 is removed; on the right, the element 2 is added concurrently with token b. After the merge, which takes the pairwise union of the add token and remove token sets, 2 remains in the set, where 1 is removed because its only add token a has been deleted. Active elements in the set are determined by identifying elements whose add token set is a strict superset of it’s removals.

Under concurrent removals, the set favors additions for the outcome of the merge. Here we show an example where concurrent additions and removals arbitrate towards addition.

As it should be clear, this design is incredibly expensive, because a set with effectively no elements can take quite a large space to represent safely.

The Observed-Remove Without Tombstones Set

The idea behind the Observed-Remove Without Tombstones Set is that we do not want to store tombstones – the remove set – for elements that we have removed from the set. However, it should be clear from the design above that if we were to just drop elements from the add and remove set – any replica that contacts us will effectively resurrect the garbage – the pruned add and remove elements. The question remained – how could we safely remove garbage from the CRDT without introducing additional coordination?

Riak’s vector clock mechanism had previously used a garbage collection mechanism that asynchronously computed – via gossip – the safe entries of a vector clock to prune based on the current membership. However, this mechanism had always been problematic under prolonged network partitions – or, stopped nodes that later resumed service – resulting in values being resurrected after thought to be pruned and the metadata around what had been garbage collected, garbage collected itself. A similar mechanism was considered for the CRDTs in Riak, but reconsidered because of these problems.

The previous work on optimized set representations for operation-based CRDT brought a further insight: the reason these CRDTs were so cheap in terms of garbage was because causal delivery ensured event visibility in a particular order. Therefore, under causal delivery, the system need not be defensive against late arriving messages – considering an event arriving after the event was supposed to be garbage collected because of a network reordering. This ordering information is maintained in the network layer wiith causal delivery – but, since Riak did not have causal delivery, could this information be encoded in the data structure itself? This is the design of the Observed-Remove Set Without Tombstones.

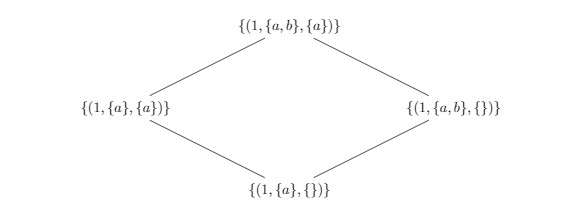

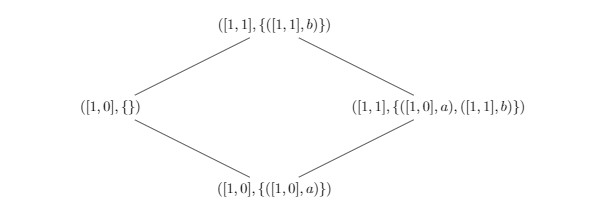

In modeling the Observed-Remove Set Without Tombstones we are going to use a pair consisting of a version vector – representing a compact version of the causal history of the object – and a payload set – containing the elements that should currently be in the set. The model will be modeled using what is referred to as dots: mappings from items in the set to entries in the version vector of when the updates occurred – inspired by the work on Dotted Version Vectors (N. Preguiça et al. 2010) by our colleagues in Portugal. When updates, like adding an element to the set, occur, we will advance the vector of the object and insert into the payload set1.

We see this below. We start with vector [1, 0] that indicates that the first actor has performed one action. In the payload, the pair ([1, 0],a) shows that at logical time [1, 0] the element a was added to the set. If the second replica performs an update operation, it increments the vector and adds the new object to the payload. Concurrently, if the first replica removes the element a, it drops the payload without advancing the clock: the clock serves as a compact representation of the causal history that says, combined with the payload, “yes, I saw this object in the past, but I don’t have it anymore, so I witnessed it’s removal.”

When the merge happens, a three-way merge is computed. We first (i.) merge the payloads; then, (ii.) we take the elements from the right that are not dominated by the left’s clock; finally, (iii.) we take the elements from the left, that are not dominated by the right’s clock. To determine the active elements in the set, the projection of the second element of each elements tuple can be used.

This results in the same outcome as described above in the Observed-Remove Set example. However, this design is clearly significantly less expensive in storage.

Object Merging in Riak

Riak stores objects either as state-based CRDTs or as plain binary objects, under a given key. Dotted version vectors at the coordinating replica for read and write operations are used to identify concurrent operations, and a merge function is used to reconcile state at the coordinating replica. When using the Last-Writer-Wins strategy, this merge function picks the object with the lexicographically greatest clock; when using CRDTs, objects are merged according to the CRDTs merge strategy; under eventual consistency, objects are merged into a set; otherwise, an arbitrary merge function may be used.

In general, the merge function used by Riak requires two strong properties: determinism and monotonicity. For each replica to arrive at the same result without coordination, the merge function must be deterministic for any two inputs. To ensure that the most recent result, depending on the aforementioned merge strategies, is eventually reached by all nodes in the cluster, the merge function must ensure that it is monotonic with respect to time in each of it’s arguments. Riak optimized it’s merge strategy so that object payloads do not need to be inspected if a version vector stored with the object indicates that one object dominates another.

In the case of state-based CRDTs, objects form bounded join-semilattices. Therefore, the merge operation is implemented as the least-upper-bound operation for the lattice.

Unsound Optimizations

Implementing CRDTs can be quite challenging. Not only does the developer who is implementing CRDTs must ensure that updates to lattices are inflationary – ensuring the data structure is always moving up the lattice with respect to each change – but also that the merge function must be both deterministic and compute the least-upper-bound. We have even got this wrong a few times ourselves.

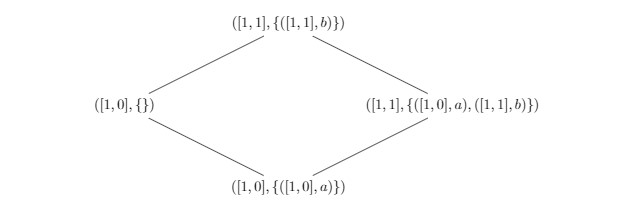

Merging is very expensive – especially, if for each read, write, and replica repair performed on the database, we must traverse the entire data structure and perform a three-way merge, as is the case with the Observed-Remove Set Without Tombstones. In an attempt to optimize the cost of merging, a change was made to the implementation to skip the merge procedure if the object currently stored had a clock that was greater than an incoming object on the network during the anti-entropy replica repair process. This methodology works for merging normal Riak objects – where each write at a replica ensures the clock is monotonically advancing – but does not work with the Observed-Remove Set Without Tombstones. Let us see why.

If we revisit our previous example, we can see that in the case of a removal – occurring with the first replica on the left, the clock is not advanced under a removal. Therefore, the ordering relation of the lattice states that a clock with a given payload object is ordered before a clock with that element not present in the payload. In short, with the optimized set representation, checking the clock alone is not sufficient for knowing whether or not a merge should occur.

This bug was reported by a user of Riak on GitHub and the commit introducing the bug reverted. The bug also has quite an interesting effect on a real system: since a set with a deleted element will always be ordered before the set with the element present, the merge operation will never accept the object with the removed elements as its clock will always be dominated by the set with the elements present – in effect, the system will believe it’s converged, without agreement from all replicas – and some nodes will never observe the removals because the operation will be ignored.

Towards Safer CRDTs (and Monotonic Programming!)

It’s very easy to get this stuff wrong. Since these bugs can be so difficult to find, work has gone into trying to make CRDTs, and systems that use CRDTs or similar properties, easier to develop and use in practice. There’s been some work done at Basho on driving a QuickCheck model to randomly try update and merge operations and ensure convergence on real implementations. There’s been some work as part of the SyncFree Consortium on the TLA+ verification of CRDTs using PlusCal and the TLC model checker. Our colleagues at Cambridge have proposed an approach to designing CRDTs using Datalog (Kleppmann, n.d.). Finally, there’s been plenty of academic work on designing correct specifications of CRDTs. (Burckhardt et al. 2014; Burckhardt et al. 2012; Gomes et al. 2017)

In terms of monotonic programming and leveraging CRDTs as part of a programming model, there’s plenty of work as well. The CALM conjecture (J. M. Hellerstein and Alvaro 2019) first made the connection between consistency and monotonic programming. Bloom (Alvaro et al. 2011) is a distributed programming model inspired by Datalog that provides monotonic programming over sets; BloomL (Conway et al. 2012) extends this model for lattice-based programming. Lasp (Meiklejohn and Van Roy 2015) is a functional programming model over CRDTs from the SyncFree group. DataFun (Arntzenius and Krishnaswami 2016) is a functional Datalog where all operations are monotonic. Finally, the high-performance Anna KVS (Wu et al. 2019) uses monotonicity internally.

At Carnegie Mellon University, in the Composable Systems lab, we have been working on a type system for verifying monotonicity of functions, that can be used to construct CRDTs from the ground up by composing together monotone (or antitone) functions. Our work is inspired by a problem we observed in LVars (Kuper and Newton 2013), Lasp, and BloomL: functions must be monotonic (or homomorphic, a special case of monotonicity) to ensure both correctness and convergence of the system; in each of these systems functions are assumed to be correctly implemented and annotated accordingly. As we demonstrated in this article, this is very difficult to get right. Not only is monotonicity difficult to get right in practice, for systems that use monotonicity, they must be high-performance and cheap. In the case of CRDTs, the Observed-Remove Set was much too expensive to actually use in practice, but it’s easy to implement and reason about. For any monotonic solution to gain adoption, it essential that the solutions be both easy to use and not prohibitively expensive.

If you’re interested in building high-performance, safe distributed systems, and you’d like to do a Ph.D with our group, you should reach out! We’re always looking for new students who want to join us.

Almeida, Paulo Sérgio, Ali Shoker, and Carlos Baquero. 2015. “Efficient State-Based Crdts by Delta-Mutation.” In International Conference on Networked Systems, 62–76. Springer.

Alvaro, Peter, Neil Conway, Joseph M Hellerstein, and William R Marczak. 2011. “Consistency Analysis in Bloom: A Calm and Collected Approach.” In CIDR, 249–60. Citeseer.

Arntzenius, Michael, and Neelakantan R Krishnaswami. 2016. “Datafun: A Functional Datalog.” In ACM Sigplan Notices, 51:214–27. 9. ACM.

Bieniusa, Annette, Marek Zawirski, Nuno M. Preguiça, Marc Shapiro, Carlos Baquero, Valter Balegas, and Sérgio Duarte. 2012. “An Optimized Conflict-Free Replicated Set.” CoRR abs/1210.3368. http://arxiv.org/abs/1210.3368.

Brown, Russell, Sean Cribbs, Christopher Meiklejohn, and Sam Elliott. 2014. “Riak Dt Map: A Composable, Convergent Replicated Dictionary.” In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Principles and Practice of Eventual Consistency, 1. ACM.

Burckhardt, Sebastian, Manuel Fähndrich, Daan Leijen, and Benjamin P Wood. 2012. “Cloud Types for Eventual Consistency.” In European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, 283–307. Springer.

Burckhardt, Sebastian, Alexey Gotsman, Hongseok Yang, and Marek Zawirski. 2014. “Replicated Data Types: Specification, Verification, Optimality.” In ACM Sigplan Notices, 49:271–84. 1. ACM.

Conway, Neil, William R Marczak, Peter Alvaro, Joseph M Hellerstein, and David Maier. 2012. “Logic and Lattices for Distributed Programming.” In Proceedings of the Third Acm Symposium on Cloud Computing, 1. ACM.

Gomes, Victor BF, Martin Kleppmann, Dominic P Mulligan, and Alastair R Beresford. 2017. “Verifying Strong Eventual Consistency in Distributed Systems.” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 1 (OOPSLA). ACM: 109.

Hellerstein, Joseph M, and Peter Alvaro. 2019. “Keeping Calm: When Distributed Consistency Is Easy.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1901.01930.

Kleppmann, Martin. n.d. “Data Structures as Queries: Expressing Crdts Using Datalog.”

Kuper, Lindsey, and Ryan R Newton. 2013. “LVars: Lattice-Based Data Structures for Deterministic Parallelism.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Acm Sigplan Workshop on Functional High-Performance Computing, 71–84. ACM.

Meiklejohn, Christopher, and Peter Van Roy. 2015. “Lasp: A Language for Distributed, Eventually Consistent Computations with Crdts.” In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Principles and Practice of Consistency for Distributed Data, 7. ACM.

“Monotonicity Types: Towards A Type System for Eventual Consistency.” n.d. http://prl.ccs.neu.edu/blog/2017/10/22/monotonicity-types-towards-a-type-system-for-eventual-consistency/.

Preguiça, Nuno, Carlos Baquero, Paulo Sérgio Almeida, Victor Fonte, and Ricardo Gonçalves. 2010. “Dotted Version Vectors: Logical Clocks for Optimistic Replication.” arXiv Preprint arXiv:1011.5808.

“Riak DT source code repository.” n.d. http://github.com/basho/riak_dt.

Wu, Chenggang, Jose Faleiro, Yihan Lin, and Joseph Hellerstein. 2019. “Anna: A Kvs for Any Scale.” IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering. IEEE.

There is some nuance here around the addition of elements at a replica that is causally ahead of another replica, where the updates must be buffered until the other object has witnessed the same causal history that is left out of this discussion.↩