Understanding why Resilience Faults in Microservice Applications Occur

In this blog post, I present results from May 2021, that were used during the development of Filibuster.

Update 2022-03-20: Based on some feedback, I realized the section on core observations was not perfectly clear. I revised that section and corrected a number of spelling and grammatical issues.

Before my automated resilience testing tool, Filibuster, was targeted at the resilience testing of microservice applications, it was targeted at the testing of distributed protocols while they were in the development phase. I referred to this process as Resilience Driven Development, whereby, faults would be introduced during development of the protocol and force developers to adapt the protocol accordingly in real-time.

The first version of Filibuster grew out of my previous Ph.D. work, Partisan. Partisan was an alternative distributed runtime for Erlang designed specifically for high-performance, large-scale distributed Erlang clusters. After I developed, benchmarked, and released Partisan as open-source, I made the observation that once you control the distributed runtime and all message transmission, you could inject faults before, during, and after processing of messages through message omission, message duplication, and message transformation. To facilitate this, I provided general hooks within Partisan, where existing testing tools could hook into before, during, and after message processing to perform arbitrary transformations. Along with this, I made sure that Partisan fixed the order of message transmission to facilitate deterministic replay when developers identified counterexamples. For demonstration purposes, I wired this up to Erlang QuickCheck/PropEr to test eventual consistency in a small application. I talked about this at Code BEAM SF 2019.

At the time, this observation seemed novel. It wasn’t; in fact, the authors of ORCHESTRA made a similar observation in 1996. Furthering my embarassment, the second author on the ORCHESTRA paper happens to be the current president of Carnegie Mellon University, where I am currently a Ph.D. student.

While my technique identified known faults in 2PC, CTP, and 3PC faster than the state-of-the-art, it required that message handlers be annotated with cumbersome annotations. While these annotations could be automatically generated using static analysis when the programs were written with academic actor langauges that used high-level message handlers, these annotations had to be manually written with commonplace actor languages, like Akka and Erlang. Since Partisan was implemented in Erlang, this posed some problems. First, it made it almost impossible to compete with existing fault injection approaches used by distributed model checkers (e.g., CMC, SAMC, FlyMC, MoDist) that provided some form automatic instrumentation and had general state space reduction techniques (e.g., DPOR, symmetry reduction.) Furthermore, the lack of an actual application corpus posed real problems when trying to perform an academic evaluation: there just simply are not enough distributed programs written in Erlang.

It was time to take a step back: can we choose a different domain where analysis might be simpler?

I decided to refocus Filibuster on microservice applications. Based on a potential collaboration with a Pittsburgh-area company that used Python for building their microservice applications, my new implementation was focused on microservices, implemented using Flask, in Python. Unfortunately, the collaboration did not pan out, so I resorted to an evaluation based on student applications. This posed a number of problems as well, with the major problem being that these student applications did not represent the types of applications that are being written in industry.

It was time to take a larger step back.

The first approach that I tried was to identify existing open-source microservice applications on GitHub, use GitHub’s revision system and issue tracker to identify any previously resolved resilience bugs, reintroduce those bugs, and then try to identify them using the new version of Filibuster. However, these applications simply do not exist in the open-source ecosystem. The ones that do exist are mostly tutorial applications that demonstrate how to properly write microservice applications; as one might imagine, these applications typically, and should not, contain bugs.

Next, I decided to take the tutorial applications and introduce resilience bugs. This is not a novel approach, in fact, it has been taken by several papers as recent as SoCC ‘21, coincidentally, where our first paper on Filibuster was published. One problem with this approach is finding the bugs: most open source discussions of bugs in postmortems or other incident reports rarely discuss the root causes of outages. This made the identification and retrofitting of existing applications with realistic bugs difficult, if impossible.

I also tried to use academic bug corpora. Bug corpora used for automatic program repair, for example, are typically constructed by harvesting programs from GitHub. These suffer from the same problem that we encountered: open-source microservice applications simply do not exist. Another possible avenue, a recent academic paper whose primary contribution is a corpora of microservice application bugs contains no bugs related to the microservice architecture itself, but contains only bugs that would exist in any monolithic web application.

I’ve written at length about these problems in a previous blog post on the lack of a bug corpus. These problems make research, into an area that I personally believe is incredibly important, quite difficult.

In this post, I am going to discuss a small research study that I performed between August 2020 and December 2020, in order to identify the types of resilience issues that companies experience and the methods that they use to go about identifying them.

Overview

If you have read my previous blog post on corpus construction, you will know that in order to solve this problem I started by scouring the internet for everything I could find on chaos engineering and resilience engineering. This served as a starting point for my work – I figured if I want to find discussion of resilience bugs and methods used to identify them, I should start by looking for discussion of the most commonly used methods to identify them today. I identified a combined 77 resources – the majority consisting of presentations from industry conferences (e.g., ChaosConf, AWS re:Invent) with a small number of blog posts. After reducing this list to 50 presentations, by eliminating duplicate presentations given at multiple conferences, presentations that contained only an overview of chaos engineering techniques, and presentations that were merely marketing for chaos engineering products, I settled on a list of 50 presentations that we used in our paper on Filibuster. This list of 50 presentations accounted for 32 different companies of all sizes in all sectors, including, but not limited to large tech firms (e.g., Microsoft, Amazon, Google), big box retailers (e.g., Walmart, Target), finanial institutions (e.g., JPMC, HSBC), and media and telecommunications companies (e.g., Conde Nast, media dpg, and Netflix.) If you are interested in the full list with direct links to each presentation, it is available from our paper.

For our published paper on Filibuster, the list was reduced even further. Here, the focus was only on presentations that met one of the following criteria:

- Was a microservice application that contained a resilience bug discussed in enough detail that we would recreate the application in a lab setting and identify the bug?

- Was a microservice application where a chaos experiment was run in order to identify bugs discussed in enough detail that we could recreate the application in a lab setting and identify the bug through functional testing with fault injection?

This left only four: Audible, Expedia, Mailchimp, and Netflix. We recreated these examples, identified bugs with Filibuster, and released a public research corpus for researchers that had the same problem as us: lack of a corpus.

In this blog post, I am going to discuss results that were not included in our paper on Filibuster and that I do not intend to publish.

So, why talk about it then? While there is not a lot of evidence to make strong claims – for all of the reasons that I outlined above – I do believe that sharing this preliminary information is useful in starting a conversation about resilience and how we go about testing for it in microservice applications. I think that this information is useful for framing how we think about resilience and I hope for two possible outcomes:

-

That an open discussion around these issues will cause developers to think differently about how they test for application resilience instead of just resorting to chaos engineering, which might not be the most appropriate technique, as discussed in a previous blog post.

-

That this will inspire sharing of information with researchers so that academics can work on relevant problems around industrial microservice application resilience. Without knowing details of bugs, application structure, and the like, academic research on microservice resilience will be non-existent or significantly behind the times.

Without further ado, let’s get into the details.

Methods

My original analysis was extremely ad-hoc. At the time of this analysis, I had not taken a qualitative nor quantative methods course. I am currently taking one right now and recommend all early-stage researchers to not put it off for more exciting courses, and front-load it to become better researchers, as I wish I had. In fact, if you are at Carnegie Mellon University, I highly recommend Laura Dabbish’s class on Advanced Research Methods in HCII. Therefore, I will frame things using the terminology of grounded theory and case study analysis; however, I did not know what these were at the time and the process was done based on a “what feels right at the time” style.

Coding

For this study, I watched all 77 presentations. For each presentation, I took notes related to application structure, testing procedures, resilience bugs discussed, the processes each organization used to identify reislience bugs, discussion of bug resolution techniques, and directions for future work. I noted several quotations from developers during this observation; this information was recorded in a shared Google document.

From here, I disregarded any discussions of organizational structure, methods or processes and technologies specific to that organization. From there, I identified what I thought were the core concepts or categories. I present them here as motivating questions that were used when analyzing my notes.

- Experiments. Did the presenter talk about an actual chaos experiment they ran to identify a bug?

- Resilience Bugs. Did the presenter talk about a resilience bug they observed or discovered (not bugs related to normal logic errors that could occur in a non-distributed application)?

- Resilience Patterns. Did the presenter talk about a pattern (e.g., circuit breaker, etc.) that they used to improve resilience of their application?

- Application Structure. Did the presenter talk about an architectural pattern in a microservice application?

From here, I further refined the sub-category of resilience bugs, based on the first analysis:

- Bug in application code.

- Bug in cloud service misconfiguration.

- Bug could have been identified using a mock, if written.

- Bug occurred in infrastructure, but was triggered by bug in the application.

I also created another sub-category of resilience bugs, based on the first analysis:

- Bugs that could have been identified using traditional testing techniques involving mocks.

- Bugs that could not have been identified using traditional testing techniques involving mocks.

Then, I created a sub-category of experiments, based on the first analysis. Reader should keep in mind that items from each presentation can belong to one or more categories in a multiple-inheritance style of analysis:

- Experiments that revealed bugs that could have been identified using traditional techniques involving mocks.

- Experiments that revealed bugs that could not have been identified using traditional techniques involving mocks.

From here, I tried to understand the relationship between the coded concepts and develop a theory about what testing methods need to be used where in order to identify different classes of resilience bugs.

For the reader who is well versed in research methods, this analysis is similar to using the constant comparative method from grounded theory when performing open, axial, and selective coding.

The Preliminary Theory

In general, many bugs that occur in software and are are identified using chaos engineering — a technique that was popularized by Netflix to test their service where faults are introduced in the live, production environment on real customers and the application’s behavior under fault is observed — could have been identified earlier using more traditional unit, integration, and functional tests in a local, development environment. However, this would require more effort on the part of the individual developer, as they are required to: identify the faults that can occur at that location, write mocks to simulate those faults, and then write the required tests with assertions. This insight served as the basis of my Service-level Fault Injection Testing technique, which combines static analysis, test generation, and functional testing.

As a specific example, Expedia tested a simple fallback pattern where, when one dependent service is unavailable and returns an error, another service is contacted instead afterwards. There is no need to run this experiment in production by terminating servers in production: a simple test that mocks the response of the dependent service and returns a failure is sufficient. However, more complicated, and more interesting, examples exist.

Example: Audible

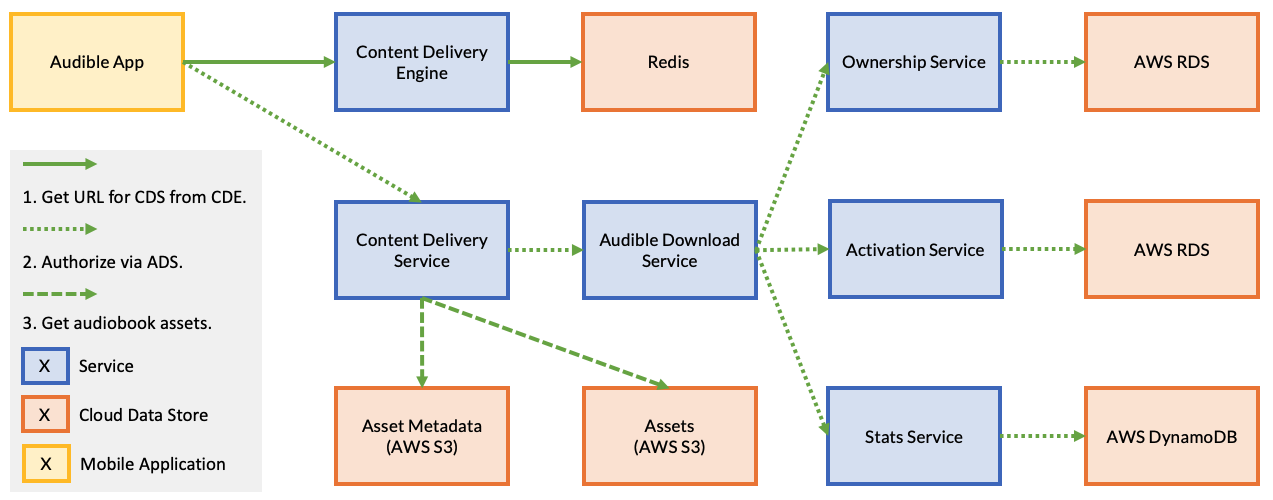

One example that was particularly interesting was Audible. The Audible example is quite complicated and involves a number of services in delivering an audiobook to an end user.

In this example, when a user requests an audiobook using the Audible app, it first issues a request to the Content Delivery Engine to find the URL of the Content Delivery Service that contains the audiobook assets; we can think of this as a primitive sharding layer that is used to support scalability. Once the Audible app retrieves this URL, it issues a request to the specified Content Delivery Service.

The Content Delivery Service first makes a request to the Audible Download Service. The Audible Download Service is responsible for first verifying that the user owns the audiobook. Next, the Audible Download Service verifies that a DRM license can be acquired for that audiobook. Finally, it updates statistics at the Stats service before returning a response to the Content Delivery Service. If either ownership of the book cannot be verified or a DRM license cannot be activated, an error response is returned to the Audible Download Service, which propagates back to the user through an error in the client.

Once the Audible Download Service completes it work, the Content Delivery Service contacts the Audio Assets service to retrieve the audiobook assets. Then, the Content Delivery Service contacts the Asset Metadata Service to retrieve the chapter descriptions. In this design, there is an implicit assumption that if an audiobook exists in the system and the assets are available, the metadata containing the chapter descriptions will also be available.

In this example — a real outage reported by Audible, the asset metadata is unavailable either because of developer error or a race condition. As a result of this, a latent bug in the Content Delivery Service that doesn’t expect the content to be unavailable if the assets are available, causes an error to be propagated back to the end user. The mobile application, not expecting this error code to ever occurs then presents a generic error to the user after retrying the request a number of times, and, after presenting a generic error to the user, causes them to hit the retry button. This influx of retries causes all of Audible to fail: the system incurs an outage. In this case, a number of software bugs — all detectable through traditional unit, integration, and functional testing, causes the system to overload and exhaust the available compute capacity in the cloud. Thus, a resulting outage.

Resilience Fault Taxonomy

When we look at this example, and the other examples from our study, we can identify there are two major concerns for the developers of microservice applications:

- First, anticipation and handling of application errors: ensuring the application contains code error handling for all possible errors.

- Second, ensuring proper behavior and scalability of resilience countermeasures: the methods that we take to contain unexpected, untested failures when they occur.

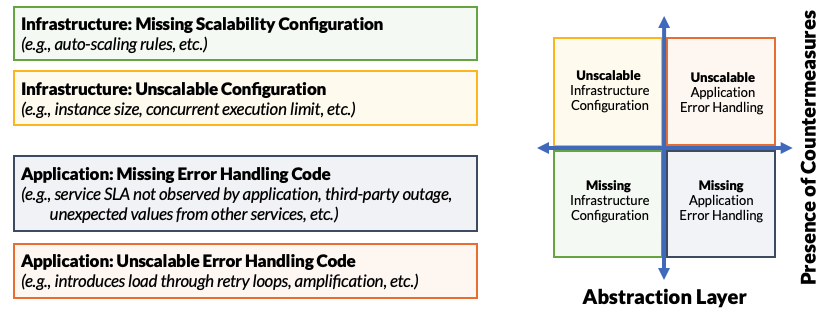

We diagram this relationship below:

We represent this as four quadrants, bifurcated by abstraction layer and whether or not resilience countermeasures are present.

- Infrastructure: Missing Scalability Configuration: Failures might occur because our system fails to handle expected load. For example, we may be missing a security policy or auto-scaling rule that is required for operation inducing external faults to our application. These external faults may trigger latent, internal faults in our application.

- Infrastructure: Unscalable Configuration: Failures might occur because our infrastructure configurations are wrong. For example, we might fail to configure auto-scaling rules or concurrent execution limits for serverless functions; this may cause our application to experience an external fault (e.g., concurrent execution limit exceeded.) These external faults may trigger latent, internal faults in our application.

- Application: Missing or Incorrect Error Handling Code: Our application may be missing or contain incorrect error handling code for possible errors: error codes we do not expect from external services, error codes we fail to handle from our own services through malfunctioning endpoints, by way of software defects, or services that are unavailable.

- Application: Unscalable Error Handling Code: Our application may contain unscalable error handling code. In this case, an error causes the application or service to take a code path designed for error handling, but that error handling path may introduce additional load on the system causing the system, or some number of the application’s services, to fail.

Ok, so what is the theory?

Theory of Resilience Testing Methods

Why does the taxonomy matter? It matters, because each quadrant needs to be addressed by a separate testing methodology with separate tools, at a different point in the software engineering lifecycle.

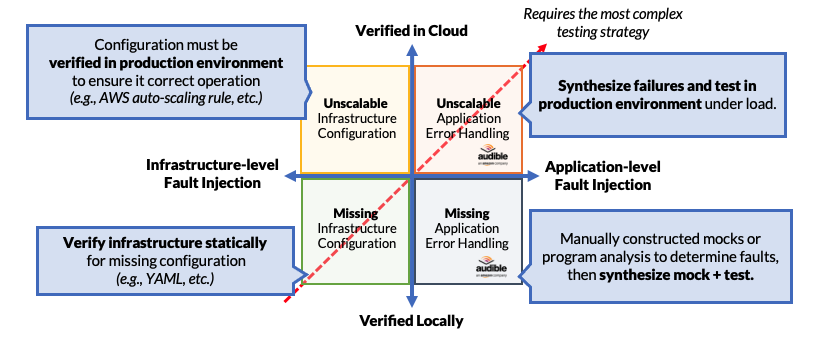

We can represent this as follows, by reimagining the same graph with different axes:

In this example, we have modified the abscissa to represent where the analysis needs to be performed; for the ordinate, we have modified it to represent whether or not we can identify the problem in a local environment or in the cloud.

When it comes to missing configurations, these can be detected locally in a development environment. In fact, missing configurations for cloud services can easily be detected through static analysis. On the other hand, missing or inorrect application error handling code can sometimes be detected statically, but most definitely detected dynamically, especially and most notably using fault-injection approaches like Filibuster.

However, when it comes to the problems of cloud configuration things change. Incorrect or unscalable cloud configurations, where auto-scaling rules or concurrent execution limits are incorrect, can only be detected in the cloud environment: we do not have this cloud runtime available locally (e.g., AWS, GCP) to detect these issues, even if we used a load generator. Since there is no way to run these services locally using those configurations, the only way to identify these issues is to run those configurations in the actual cloud environment under either actual or synthetic load. In fact, we may need to inject infrastructure-level faults to do proper testing; for example, inducing instance failures to trigger an instance restart rule to fire. We note that Azure has made some movement in this area by allowing them to run their serverless runtime environment locally.

When it comes to incorrect, or unscalable cloud configurations, that only cause faults under a latent application fault, these failures must be tested in the cloud environment when we can induce faults. While chaos engineering can identify a number of these faults when they occur in the infrastructure – through failed instances or blackholed DNS – all of these failures surface themselves as errors or exceptions in the application, which indicates that we should inject these failures in a cloud environment to identify them, in the application where they can be explicitly controlled and exercised.

Core Observation

Testing complexity increases as we move towards the upper-right quadrant.

As we move towards that direction, we need to run the applications in a cloud environment combined with principled fault injection. For simple infrastruture-level faults, this can be as simple as crashing a service. For application-level faults, more advanced techniques are required. For instance, causing a particular service to fail with a particular GRPC response code that then causes the invokers of that service perform more expensive, alternate work.

Chaos engineering, a technique that works well for the upper-right quadarant, is commonly used for identifying issues across all quadrants. It is sufficient, but not necessary.

To understand this, we use a small example. Consider the case where Service A takes a dependency on Service B.

- If A fails to handle the unavailability of B, or does not handle its failure properly, we should detect that locally. That lives in the lower-right quadrant.

- However, if upon experiencing a failure of Service B, Service A invokes a more expensive code path that, under load, crashes because of incorrect service provisioning or resource exhaustion, that’s the upper-right.

Chaos engineering is the hammer and all four quadrants look like nails. It works because is operates at such a low, fundamental level. While it is sufficient, it is not stricly necessary, for identifying these classes of resilience issues. Instead of resorting to chaos engineering for identifying all resilience issues, a multi-lvel testing approach should be used in order to identify failure to handle errors first, ensure proper handling of errors, before testing these error handling and resilience countermeasures in the cloud environment.

Takeaways

What are the takeaways?

- Failures can occur because of both infrastructure and application-level problems. Therefore, a multi-level testing approach is necessary to address both.

- Application-level problems, such as the problems in the Audible example, can result in outages if left unhandled and then propagate to the infrastructure-level. Therefore, try to eliminate as many problems as possible through local testing and then use testing in the cloud, under load with principled fault injection to determine if the system reacts to failures under load correctly.

- Infrastructure-level misconfigurations should be detected statically, if possible, using configuration validation tools. Verifying these configurations should be done using load testing tools, based on expected load, in the actual cloud environment.

If you find this work interesting, please reach out. I’d love to hear more about application designs, failures, outages, and anything related to microservice resilience.